Circuit Debugging

Circuit network can be used to create complex behavior. Circuits operate very quickly, changing 60 times per second (every 0.017 seconds which is called as "tick"), making it impossible to follow their behavior with the naked eye. If something doesn't work as expected, this is not a problem for simple circuits, but when it comes to complex circuits, it can be difficult to investigate what is happening. I have devised a mechanism within the Factorio game that allows you to step through the operation of a circuit, which is useful for debugging, and I would like to introduce it here.

Stepping through the editor

I found out after writing this, but there's actually an easy way to step through.

First, run the /editor command (in game editor). The key binding is Control+Shift+F11. When you enter editor mode, the game will be paused by default. You can switch between resume and pause by pressing "0" on the numeric keypad. When paused, pressing "." on the numeric keypad will step through.

If this method exists, the information below is not very useful, but I've taken the time to write it, so I'll leave it here in case it's useful in some way.

If you want a quicker way to use it, see Step execution circuit.

Switch

What we want to achieve is a mechanism where the circuit's operation advances by one step each time a button is pressed, and then remains paused until the button is pressed again. We will introduce a "switch" circuit that will be useful for such operations. BP for this circuit is here

The mechanism of this circuit is simple, so I will not explain it here. To use it, first place one deconstruction planner in the center. Any item will do, but I used a deconstruction planner, which is not often used as an item, so that it does not overlap with other items. You can create as many deconstruction planners as you want without using materials by clicking the red X icon in the bottom right of the screen. Hold it in your hand and place it on the belt with the Z key. Point the mouse cursor at the belt in the center and press the R key; it will alternate between ON and OFF each time you press the key. The lamp is simply there to make it easier to see the ON/OFF status, and you will need to wire it further into the circuit from here to use it.

Latch circuit

A latch circuit holds the contents of a signal (information) for a certain period of time and resets it to its original state with a reset signal. The circuit below is intended to explain the operation of a latch. Click here for the BP of this circuit.

The decider combinator is set up as follows:

Place one iron plate on the left switch, and one deconstruction planner on the right switch. First, set both lamps to off. Next, when the left switch is turned ON, the information "Iron Plate=1" is input to the latch input (red cable side). Next, even if the left switch is turned OFF, the latch output remains as Iron Plate=1. In other words, it remembers the contents of the signal. Next, when the right switch is turned ON, the information disappears and returns to normal.

One-shot circuit

The latch circuit above can remember the type of signal (which item), but the value is always set to 1. The circuit we are looking for is one that remembers not only the type of input signal, but also the value. If the output configuration of the decider combinator is set to "input value" instead of "1", the value can be remembered as well, but this only lasts for the first tick, and from the next tick onwards it becomes the sum of the previous value, so it does not work as expected. Therefore, we will create a circuit that turns ON for just one tick when the switch is turned ON, and then the output will turn OFF even if the switch remains ON. Click here for the BP of this circuit

As before, place one iron plate on the left switch, and one deconstruction planner on the right switch. The condition circuit on the left is set up as shown below, simply outputting the input as is.

This decider combinator does nothing, but it takes one tick to transmit from input to output. In other words, the ON/OFF change of the input is transmitted directly to the output side, but with a one-tick delay. The setting for the decider combinator in the middle is shown below.

The input to the red cable (hereafter referred to as R) is the original ON/OFF signal of the switch, and the green cable (hereafter referred to as G) is one with the timing delayed by one tick. The conditions are R: each ≠ 0 and G: each = 0. "Each" (the yellow icon with three lines in the box) means that the same calculation is performed for each different item, and since there are only iron plates here, it is the same as reading it as "iron plates". When the switch is changed from OFF to ON, the R side turns ON immediately, but the G side is delayed by one tick, so for the first tick only, Iron Plate ≠ 0 on the R side and Iron Plate = 0 on the G side, and Iron Plate=1 is output. At other times, there is no signal.

The decider combinator on the right, as shown below, changes the output setting of the latch circuit to the number of inputs.

The decider combinator in the middle outputs only the first tick of the original input signal, so the original signal can be accurately memorized. By turning on the switch on the right, the memory can be cleared and restored to its original state.

Improvements

I was able to embody most of my ideas in the above, but I would like to improve the following:

1. In the final step execution circuit, all decider combinator, arithmetic combinator, and selector combinator used in the original circuit will be replaced with step execution types. Therefore, we want to reduce the number of parts by separating the part that generates the timing signal from the latch-related part and sharing the timing signal circuit.

2. In the above circuit, step execution only occurs when the switch on which the deconstruction planner is placed is turned OFF=>ON. This makes it difficult to operate, so we will make it so that step execution occurs both when OFF=>ON and when ON=>OFF.

3. The output terminal resulting from step execution will be connected to other circuits, so a mechanism is required to avoid interference such as short circuits with other circuits.

The final version, taking these improvements into account, is shown below.

Step execution circuit

The step execution circuit is shown below. The left half is the timing signal generation circuit, and the right half is the latch circuit. The circuit on the right is made by placing multiple identical circuits for all the decider combinator, arithmetic combinator, and selector combinator of the original circuit and connecting them together. The BP for this circuit is here

Don't forget to place a deconstruction planner in the center of the left switch. Items placed on top of it are not subject to BP.

The combinator's configurations are shown below, starting from the top left and working downwards.

The first decider combinator delays the Step Switch signal by one tick.

The second decider combinator outputs a "OK" signal for one tick only when the Step Switch changes from OFF to ON and from ON to OFF. The first and second decider combinator generate one-shot signals for the one-shot circuit already explained.

The third decider combinator outputs a "OK" signal at the exact opposite timing to the previous one. This signal is used as a clear signal to clear the information stored in the latch circuit.

Next, the combinator's configurations are shown below, starting from the top right and working downwards.

The fourth decider combinator captures the output of the original circuit and outputs it for just one tick, the moment the Step Switch changes, and does not output anything at other times. By combining this with the one-shot signal above, a one-shot circuit is realized.

The fifth decider combinator is a latch circuit that keeps the signal obtained by the fourth decider combinator and continues to output the same signal. The signal is cleared the next time the Step Switch changes. The moment the step switch changes, the fourth decider combinator stores this information, and at the same time, the fifth decider combinator erases the value it had stored just before. These operations are performed simultaneously, and the next tick sends information from the fourth decider combinator to the fifth decider combinator, which stores it.

The sixth decider combinator does nothing but transmits the input to the output. It does nothing, but without this, the output of the fifth decider combinator would be connected to another circuit, and a signal would then flow in from there to the input of the fifth decider combinator, causing interference. This is necessary to prevent this.

Can you understand how this results in step execution of a circuit? A look at the example of a counter circuit in the next section will help you understand. In the original circuit, the output of the circuit is connected to the input of another circuit, and signals are transmitted one tick at a time, causing the overall circuit to change at a dizzying speed. With this step execution circuit, the output of the original circuit is taken in and transmitted to the other circuit only when the step switch changes, so the output of each circuit does not change unless the step switch is operated.

Example of using a step execution circuit

To explain how to use it, let's step through the following counter circuit. The BP for this circuit is here.

This circuit adds up the variable T=1 generated from the constant combinator every tick and counts up as 0, 1, 2, ... Then it resets every 10 ticks and starts counting again from 0. The lamp has a condition set to T<5, so the lamp lights up between 1 and 4 and goes out at other times, so it flashes quickly.

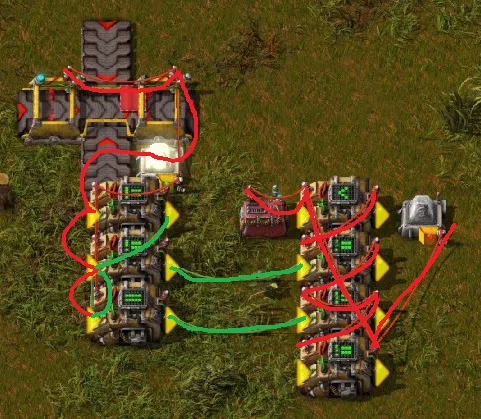

Naturally, the circuit as is cannot be executed in a stepwise manner. The original circuit needs to be modified to be able to execute in a stepwise manner. The modified circuit is shown below. The BP for this circuit is here

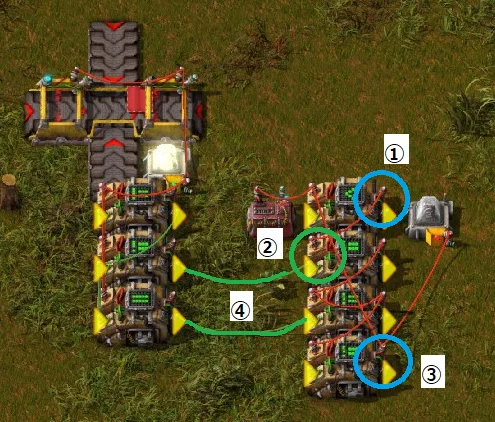

Place one deconstruction planner in the center of the left switch. There are a total of seven decider combinators, but the decider combinator in the upper right corner is the one that was included in the original circuit before the modification. The combinator's settings are also exactly the same as the original circuit. The remaining six decider combinators are the step execution circuits shown in the previous section.

To convert the original circuit into a step execution type,

1. Place the step switch and timing signal generation circuit of the step execution circuit. (Left half of the diagram)

2. Leave some space below all the decider combinators, arithmetic combinators, and selector combinators included in the original circuit.

3. Place the latch circuits of the step execution circuit below each of these combinators, etc. (The three decider combinators at the bottom right)

4. Rewire all of the wires that were connected to (1) in the diagram to terminal (3). Without changing the color of the cables, connect the red cable that was originally connected to (1) to terminal (3) instead, and similarly connect the green cable to terminal (3) with a green cable. For example, originally a red cable was connected between (1) and the lamp, but delete this and instead connect a red cable between (3) and the lamp.

5. Connect (1) and (2) with a red cable.

6. Connect the two wires at (4) with a green cable.

Let's try it out. Below, the decider combinators included in the original circuit (top right) has been opened and the details are being viewed. The variable T is initially set to T=1. This is equal to the output of the constant combinator, which indicates that the output of the previous decider combinator was T=0.

Pressing the r key in the center of the step switch will advance the circuit processing by one step, and T=2 will be reached.

If you repeat this several times, you can confirm that the light goes out when T=5 is reached, as shown below.

In this way, when using step execution, the circuit operation will advance by one tick each time the step switch is operated, and then stop at that state. Debugging can be done by advancing by one tick and examining the state of the signals in each part.

Step execution of the last "Step execution circuit"

In theory, a step execution circuit should be able to step execute any circuit. If so, it should also be possible to step execute the "Step execution circuit of a counter circuit" introduced above. A circuit that achieves this is shown below. Click here for the BP of this circuit.

The switch on the top left causes the entire circuit to step, and to the right of it is the step switch within the "Step execution circuit of a counter circuit." First, operate the right switch (rotate it 45 degrees from the center with the r key). This gives the command to step the counter circuit, but at this stage the "Step execution circuit of a counter circuit" remains stopped, so nothing happens. However, if you open the decider combinator at the top of each column and check its output, you can see the changes that are scheduled to occur next. Next, operate the left switch. This causes the "Step execution circuit of a counter circuit" to move forward one tick and detect a change in the right switch, but the counter value does not yet change. After operating the left switch for a total of three ticks, the counter finally operates and the value of variable T changes. It's a little complicated, but step execution works as expected.

The example shown here is not very practical, but I have included it here for reference to demonstrate that any circuit can be step-executed. As the number of original circuits increases by about four times, the drawback is that it inevitably becomes more complex. However, being able to step-execute any circuit and examine it in detail is useful, and it is a helpful tool, so I hope you will make use of it.